Why Black History Month Matters

Progress in America has never been a straight line, as President Barack Obama remarked after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016. We zig and zag, sometimes forward, sometimes back. The way we teach American history is no different. We move ahead, and then fall back. Look at the zigs and zags in the study of Black history, now under fire in Florida and other states.

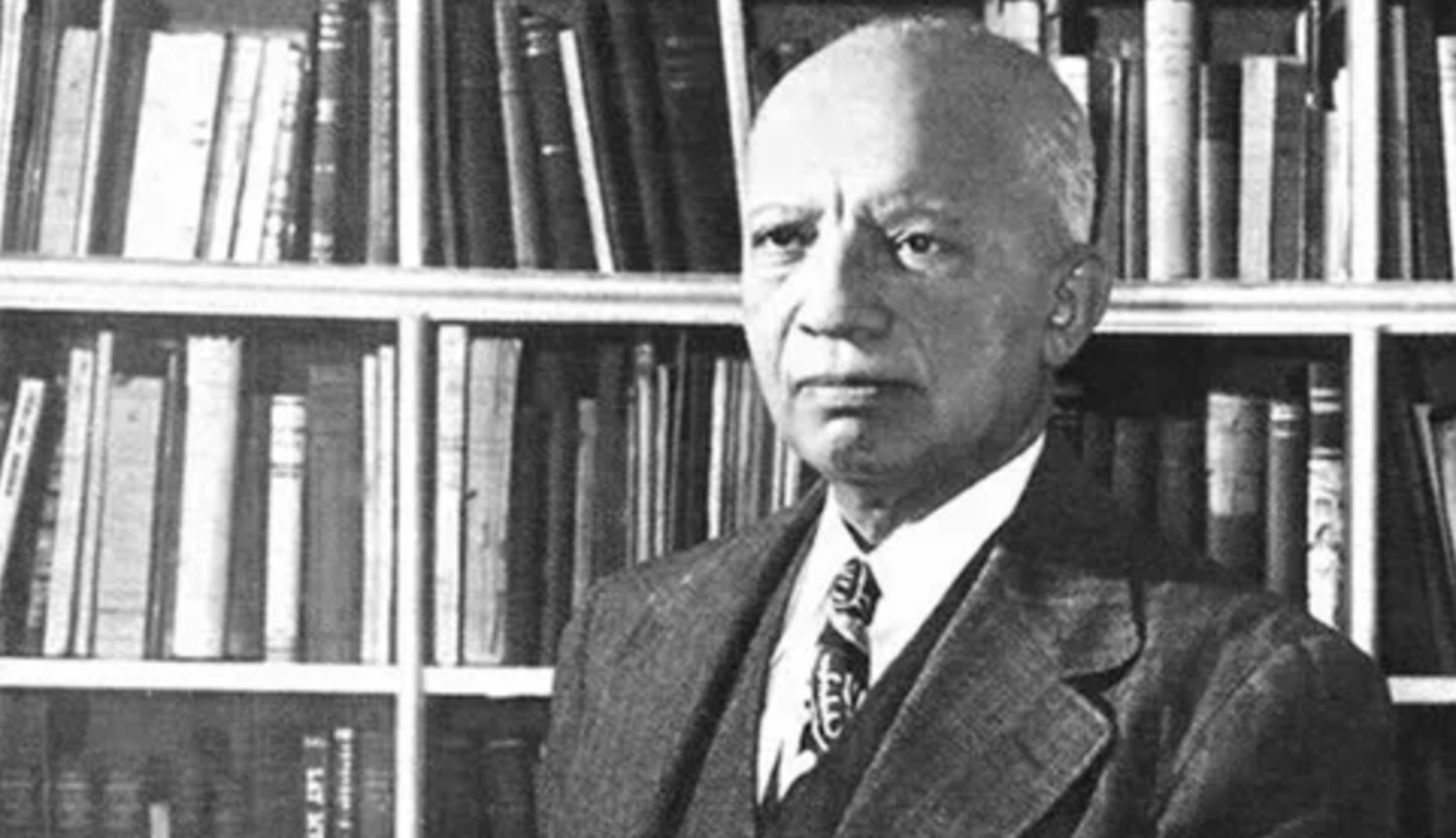

Black History Month, the practice of setting aside the month of February to highlight the contributions of African-Americans, has its roots in Negro History Week, founded by Carter G. Woodson in 1926. At the time, children’s history textbooks in both the North and the South routinely depicted slavery as a benign institution, even a benefit to the slaves.

As historian Donald Yacovone writes in his new book, Teaching White Supremacy: American’s Democratic Ordeal and the Forging of Our National Identity, most children’s textbooks from the 1920s through the 1960s described kindly masters providing enslaved people with plenty of food, comfortable cabins, and happy evenings spent singing and playing the banjo around a campfire.

Slavery, one textbook insisted, had improved the lot of enslaved people because “it was better for the negro to be a civilized slave…than to be a savage in the jungle of Africa.” For decades, Yacovone writes, children’s history books either ignored Reconstruction or depicted it as a time when power devolved to people who “were so ignorant and inexperienced that they hardly know what to do with their freedom.” Textbooks depicted the Klu Klux Klan as a “sort of police” that “ended the tyranny of black rule.”

Woodson, one of the first Black men to receive a PhD in history from Harvard University, provided an antidote to these toxic lessons—at least for Black children in segregated schools. His 1920s textbooks, including The Negro in Our History and Negro Makers of History for Young Readers, were widely adopted by public school systems for their “colored” schools. These books boosted racial pride and gave a realistic account of the role of Blacks in U.S. history.

Most white children, however, continued to learn from books that depicted Blacks as inferior. Only in the late 1960s and 1970s did most history books begin to change, influenced by the Civil Rights movement, Yacovone writes. Textbooks began to include the contributions of Black leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Phillis Wheatley and Benjamin Banneker and, for the first time, African-Americans were depicted as “fully human.” In 1976, Negro History Week evolved into Black History Month.

Today, there is a backlash against efforts to teach children the central role that slavery and racism play in U.S. history. Thirty-six states have adopted or introduced laws that restrict teaching about race and racism. Florida will not allow high schools to offer a new Advanced Placement course in African American studies.

And yet there is compelling evidence that children need to know more history. Just 8 percent of a thousand students surveyed by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2018 could identify slavery as the cause of the Civil War, as Yacovone points out. And it’s not only children who are ignorant: Half the medical students and residents in a 2016 Duke University survey believed African Americans have thicker skin and less sensitive nerve endings than whites.

On the positive side, teachers no longer need to rely on textbooks to give their students an understanding of U.S. history. Organizations such as the Zinn Education Project, the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History, and the 1619 Project offer free online lesson plans and documents.

Nearly 100 years since Woodson founded Negro History Week, we need Black History Month more than ever. Indeed, we need to study Black history year-round, not just in the month of February.

Clara Hemphill, the founder of InsideSchools, is the author of A Brighter Choice: Building a Just School in an Unequal City.

Photo from the National Park Service

Please Post Comments